Jewish Knife Grinder - Odessa - circa 1890

I can honestly say, after 36 years as a smith and 25 of those years as a blade smith, I am still learning something all the time, but am definitely beginning to understand what ⇒Baron Humbert von Gikkingen said : “If a craftsman puts his whole heart into a creation, he gives it a soul.”

Photos at bottom

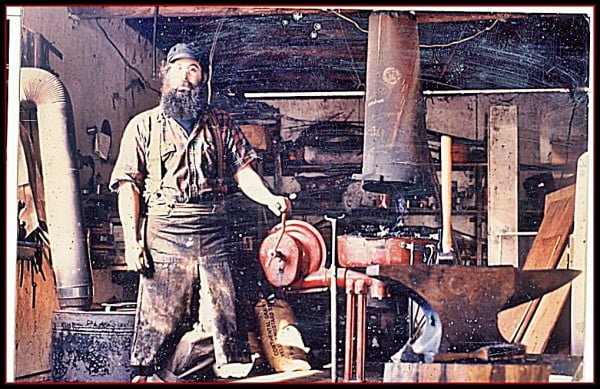

In 1979, local Oregon blacksmith/farrier Jim Rich, offered me an open ended apprenticeship after I paid him for a three week class. I lived at the forge, swung a sledge hammer when called for, and learned all aspects of forging and smith-ing in a non electrified shop. I lived next to the forge in a log cabin without bathroom, power or water. I learned forging and design techniques , as well as horse shoeing and wagon making. After finishing this one year long traditional ‘apprenticeship’, I made forged “house jewelry” for three years, selling my work at low end craft fairs.

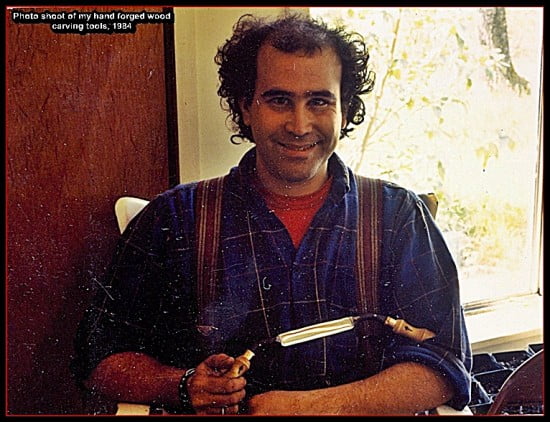

By 1983, I decided to start working with high carbon tool steel , and looked around for further training. In considering another apprenticeship, I spent a few amazing days with a master tool smith who forged a beautiful line of wood carving tools that were so fine. His name was Dick Anderson from Washington state and I salute his fine craftsmanship. I decided after this visit that the end cost was not affordable for me, so I opted for more training in my own shop - or flying by the seat of my pants. I wrote many letters asking for advice and help, at that time, but not one person replied. If I was going to expand my skills, it was on me to do it. I knew it would take more time, but this was going to be my path.

So I spent 2 years of my spare time beyond producing house jewelry for sale at shows, getting ready to produce fine woodcarving tools. These were fully forged, by hand, from round high carbon tool steel bar called drill rod. This meant that I had to refine my forging technique as forging tool steel leaves no room for error. At the same time I began making a 7 foot line shaft, with 5 stations run off of a 1 hp electric motor. The shaft ran on i - beams and pillow blocks, using pulleys and belts to power each station. Each V- belt (like on a car - not a flat belt) was connected to a station which had a pair of pillow blocks which has grinding/buffing/polishing wheels on them. I would forge a tool, and then move along each station refining the surface and edge with each station. The grinding stations had two 12” x 2” grinding wheels.

Then there was the carving tool designs themselves to figure out, which meant learning wood carving. A steep never boring learning curve, which took two years to get to the point where I could confidently market the tools. I also had to make dies that would slip into my forging vice, which I could use to mold sweeps into my gouges.

Subsequently, I made these forged tools full time for 7 years . These included, in all sizes – traditional and modern hand and D adzes (some designs learned from a Kahune on Big Island of Hawaii named Sam Kaii), chisels and gouges of all sweeps and designs, scorps, draw knives, 15 different carving knives, and many other specialty tools for violin makers, log cabin builders, etc. From this, it was a natural leap for me to make kitchen knives and sell them at shows, as people encouraged me to copy their knives. They sold well enough that I found myself transitioning to blade smithing, eventually focusing on just kitchen knives by 1990.

I only use carbon steel for obvious reasons, considering my training with tools made from the same steel. Edge tools are edge tools.